Code

system("./figures-and-tables/postcol/colog-data.sh")Towards a formal framework for bending singularities in humanity’s favour

Good Enough Data & Systems Lab

Patrick Robotham, Data scientist

Good Enough Data & Systems Lab

James P. Morris, Data Scientist

Good Enough Data & Systems Lab

Dr Garima Gupta, Ecologist

Good Enough Data & Systems Lab

May 17, 2025

If the analyst cannot find, access, interoperate with, and reuse data representing people, then it becomes very difficult for that analyst to faithfully represent the people the analysis is meant to serve. Figure 1 formalises how human intent is lost in structured intelligence systems when data is unavailable to the analyst.

When we can see how systems are failing our intentions, we are more likely to turn our attention from the wrong questions, to the imperatives of reality, such as climate change and inequality. We need to trace representations of human intention to ensure results are as humans intended.

A colog may be thought of as a contextual representation, to at least one person, of an assumption that may not hold.

By defining and applying this construction, we demonstrate the necessity for a critical but computationally implementable response to ethics in technology. That is: we need ethics expressed in logic, if we are to encode justice in the systems that increasingly govern our lives.

We propose cologs as governance primitives for exposing—and ultimately mitigating—epistemic injustice in data infrastructures.

Our purpose is to apply this framing to an open science problem in order to explain the utility of the following construction.

Definition 1 Representation category

A representation category models the structure of an assumption as a categorical diagram with:

representation: a symbolic or formal artifact (e.g. chart, document, data)represented: the real-world entity or concept the representation refers torepresentor: the agent (typically human) who creates or interprets the representationrepresentor → representation: the representation is created or selected by the representorrepresented → representation: the representation is intended to encode or reflect the representedrepresented → representor: the representor is assumed to understand the representedA representation category is embedded into a structured intelligence system via a functor or diagram that assigns these roles and relations to instantiated system elements. Morphisms may be annotated as non-functional, non-commutative, or unjust to signal representational failure or epistemic injustice.

Definition 2 A colog (critical olog) diagrammatically exposes assumptions in an analysis that do not hold about a representation.

A colog is a projection of a category-theoretic olog, as defined by Spivak [1] where objects are elements of a system and at least one object is a human.

A colog is constructed by applying at least one representation category for each assumption, and summarising the results at the representational level.

Crucial to the craft of cologging is to constantly challenge what is truth and what is assumption.

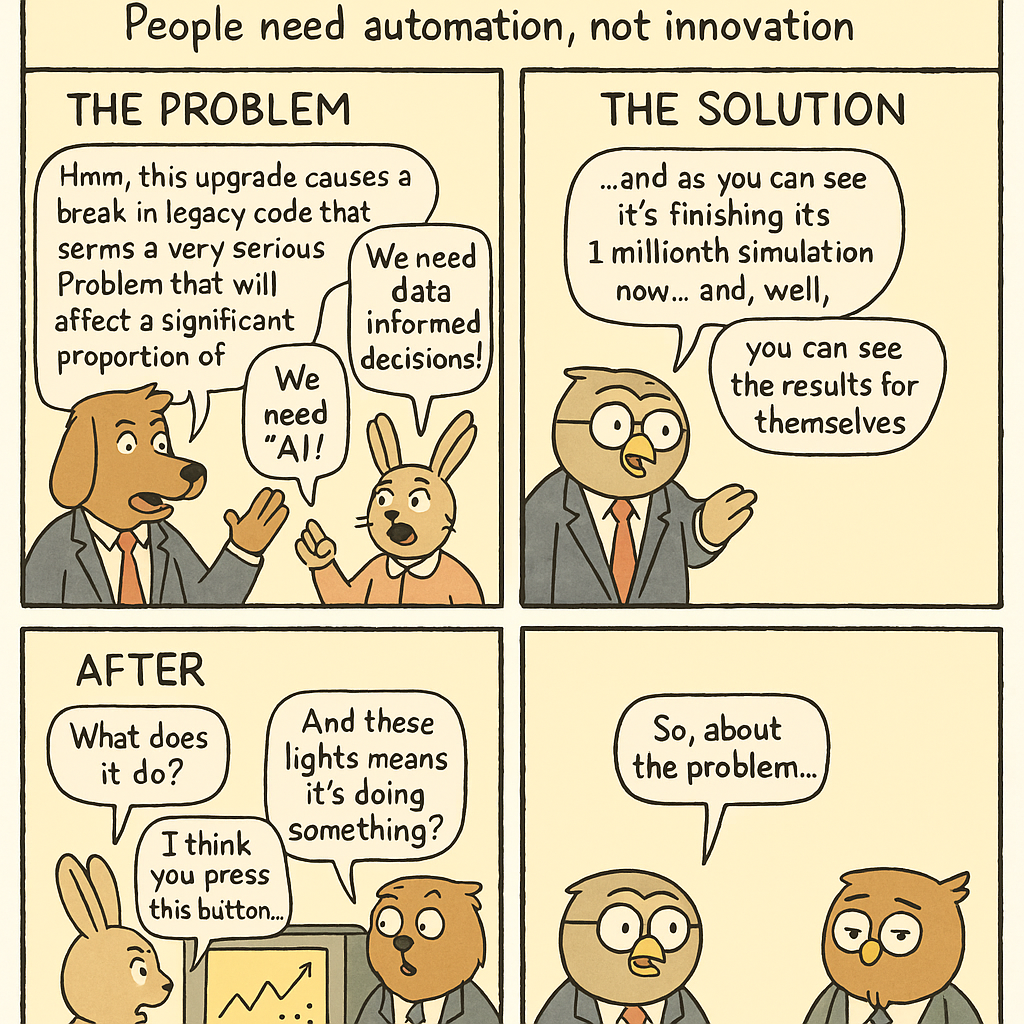

A widespread assumption is that getting the data is a process akin to a chicken laying an egg, when it is a science as challenging as any applied, as are many of the dark arts of data. We have critical problems in technology, but the zeitgeist feels flooded with “agentic AI” and “vibe coding” hype. At the Good Enough Lab, we think of this as math and code.

As a person who works with data, it can feel like everyone in the world is arguing about when machine thinking will overtake humans in a singularity event.

I never found this compelling, for it assumes an intentional determinism I don’t believe follows for, say, natural language processing, such as ChatGPT[2].

A technological singularity event didn’t sit with my training in computational complexity applied to statistical algorithms understood as golems [3] 1.

Indeed, leading metascientists now claim to have shown human cognition is computationally intractable [4]; that’s mathspeak for there is no such thing as artificial intelligence.

I’ve always been more concerned by the chaotic nature of data stacks, and how little interest there was in governance, relative to science fiction hype (Figure 2).

I constantly worry about the consequences of ungoverned systems for humans: identity theft [6]; discrimination; and my perpetual bugbear, the fiction we have automated when in point of fact the work, and potentially catastrophic emergent cost [7], has been pushed to the unpaid end user.

A singularity *event* is science fiction. However,

singularitiesare already woven into the fabric of humanity’s existence. We have always lived in largely-benign singularities (Figure 3), where heuristic and intentional systems interoperate via humans to produce emergent effects; it is only that scale now makes systems powerful in a way they never were before.

We must recognize that the challenge is not to prevent a singularity, but to govern the singularities we are already part of, harnessing this power for good, rather than allowing unchecked evils to emerge.

In order to instantiate ethics computationally, we need to translate to logical statements (predicates) a computer can understand. We provide our first definition of many; each of which is part of this living document, to be discussed and updated as new community join the Good Enough Lab.

Definition 3 Structured Intelligence System (SIS)

A system composed of humans, automata, and the heuristics by which they interoperate, producing emergent effects.

A world obsessed with the singularity has only now realized that governance is the missing piece. We need a formal foundation for structured intelligence [8] governance before chaos overtakes order, and humans cannot do this without machine help.

Definition 4 Structured Intelligence Governance (SIG)

Structured Intelligence Governance (SIG) is the principled coordination of a Structured Intelligence System (SIS), ensuring that the interoperations between humans and automata are governed by just, intentional rules. SIG aims to prevent epistemic drift and emergent harm by aligning heuristic action with human intent.

The dinosaurs of technology are out of the park and it is going to take the combined efforts of critical theorists, mathematicians, developers, data scientists, and decision makers to get the raptors back into the enclosure (Figure 4).

A government is a body of people, usually, notably ungoverned. –Shepherd Book ([10])

The intelligence of a structured intelligence system is only as good as the human’s ability to interoperate within the singularity. If knowledge is power, then human empowerment suffers epistemic injustice, injustice related to knowledge, when data systems fail to provide the knowledge a human needs reliably. Data development is implemented by humans, usually, notably ungoverned.

We think structured intelligence governance falls more in the subcategory of epistemological injustice within the theories of epistemic injustice, however there are aspects of systems epistemology that also fall into testimonial or hermeneutical injustice [11]. However, it’s not for us to say, for we are not experts in epistemic injustice.

We will need the help of those theorists in examining epistemic injustice of inaccess to data. For example, standard information technology procedures, such as the principle of least privilege [12], wherein access is granted on a needs basis, can create barriers to data when the stakeholder does not know which data to request.

Our intention is to build bridges from the world of data science system design to people who understand how to write better rules for structured intelligence systems.

One—just one!—way of examining epistemic injustice in data systems is to ask if the system is findable, accessible, interoperable, reusable (FAIR) for domain-knowledge analysts who design questions and answers [13].

| FAIR principle | Minimal interpretation |

|---|---|

| Findable | Person can find the analysis from their machine in a way that makes sense to them. |

| Accessible | Person can interpret what they see in a way that makes sense to them. |

| Interoperable | Person can manipulate the analysis in ways specific to their role. |

| Reusable | Person can reuse analysis components for future work. |

We propose, as for example, that a visual guide for surfacing what is jointly understood in terms of domain-specific variables that are:

This structured intelligence system must be FAIR to each human within the system. We propose clopen analytics (Definition 5), in opposition to the principle of least privilege, wherein access is granted on a justified needs basis [12].

When the technology itself is a barrier to knowledge, we must question if its application achieves the outcome intended.

If the principle of least privilege applies, then the default is epistemic exclusion—a structurally encoded barrier to intentional access.

Definition 5 Clopen analytics.

FAIR SIS

Clopen analytics is an approach to living analysis development SIS that prioritises making the following artifacts FAIR to each human in the SIS:

Contextual to human

FAIR is contextual to each human’s requirements for interoperating in the SIS.

Clopen

The SIS is secure and closed to those who do not require access to this SIS; for humans within the SIS, open-source community frameworks apply.

Without a shared understanding of the domain-specific variables and other FAIR principles met for each member of the team, those with the most at stake are largely locked out. Team members with the domain-specific questions to answer cannot guide the analysis through inquiry, and data developers are confused by constantly-changing requirements.

Furthermore, we need to standardise knowledge-transfer methodologies so that computational instances may follow critical-theoretic frameworks designed to prevent epistemic injustice.

And the Good Enough Lab want to hear what she has to say.

Dr Garima Gupta is environmental ecologist who speaks about systemic injustice in her local communities of origin. She has a lived-experienced point of view of how top-down implementation of sustainable development epistemically drifts away from community priorities. I cannot think of a voice I would want to learn about these issues from more.

FAIR for Garima that migrates her current barchart with a couple of small tweaks has a surprising amount of requirements and tasks.

We could explore the data ourselves, but this locks Garima out, and Garima is person who knows what whe wants to explore in the data.

At the Good Enough Data & Systems Lab, we consider anything that only runs on our own laptop not contributing to progress (yet). Our intention is to empower Garima as an applied scientific analyst to design her own questions and lines of inquirty that may or may not involve computational collaboration.

We aim to convince you that humans must learn to interoperate with other humans via technologically more intelligently or epistemic injustice is mathematically exposable—that is, we can measure and visualise aspects readily.

We require formalism to explain and make inference about universal epistemic injustice, however it is our endeavour to do so in minimal presentations. We do not try to reach beyond what might be covered in the first seminar of any postgraduate field. We admire the spirit of Category Theory for the Sciences (we are studying chapter 2) that formalises not for intellectual flourish, but to explain universalities across contexts, cutting across semantic reinvention of each other’s wheels [1].

We build systems for people to interoperate with each other in what feels like a dark room; by formalising our computation we hope to expose plug-and-play interoperabilities with those who can help us write just rules into the systems that govern our lives—humanity must learn to bend the spoon together to govern the chaos of the singularities we live in.

Critical theory is now coinciding with category theory in philosophy [14], allowing for a rich formal framework to apply constraints defined by scholars who have studied the harms of humans blindly defaulting to heuristic social norms in race [15], gender [16], and class [17]2. This manuscript endeavours toward minimal representations of conceptual frameworks, so we take the most canonical governance measure on machines, systems should not harm humans, as exemplar canonical of critical-theoretic governance frameworks for human-machine interoperation.

It is fitting that, then to focus on 1. from Asimov’s three laws (Definition 6) as inspiration for how we might govern chaos in how humans interoperate with technology [18].

Definition 6 Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics

Now as noted, there are no robots, nor will there ever be [4]. But I am in a singularity with my device when logging into a system such as a bank3. There is me, a human object, and a technological device.

If that technological device forces the human to deviate from their governance framework (such as protect my own privacy) through repetive changes to how we interface, humans become fatigued, and look for other paths. Those paths may well be less secure than the governing principle of protecting our own privacy. MFA is a step in the right direction, but humans remain overwhelmed by the process of logging in.

To diagnose what is unjust about the system, we first need to agree upon what the system is.

Definition 7 Structured intelligence system

A structured intelligence system comprises:

We are concerned with unintended emergences that render structured intelligence systems harmful.

Definition 8 Singularity

A singularity represents a structured intelligence system of humans and automata that interoperate by heuristic and intentional relationships in which complexity of interoperation produces unexpected emergence.

A structured intelligence system [8] is a system of humans, automata, and the interoperations of humans and automata.

Definition 9 The first law of structured intelligence governance

Now, developers of technology do not intend harm, and yet, I find myself so fatigued by changes to how we log securely into systems even I cut corners I know I shouldn’t with my own data.

There is a mismatch between the intended functionality of security, to protect humans, and the outcome, an unmanageable deluge of workflow constantly in flux. This is not just a mismatch, but antithetical to intention.

We now loosely introduce another key concept, how the harm can be thought of in the epistemic drift between intention for privacy measures to increase security and wellbeing and how the outcome produces neither.

Asimov is a canonical example—a Google Scholar search for asimov's laws in literary theory yielded 17,200 results—within literary theory pointing to an ocean of knowledge we not interoperating with. We genre-switch for this section to critical-theoretic framing to explain the concept of epistemic drift.

Postmodern frameworks provide theorists with a way of differentiating between a thing and its representation, notably which must be constructed by humans describing the thing. Any representation necessarily loses information, mathematically we would say a representation is a projection. Critical theory thus provides powerful ways of understanding epistemic drift.

Consider the intention of composers in the nineteenth century to ride the wave of exoticism and capture the sound of the orient [19]. This was prior to sound recordings. Instead, some composers were lucky enough to be present at the Paris Exhibition of 1889 and hear the music of the “Street of Cairo” [20]. Other composers, imitated the music of those composers, baking in an ever-diluted musical conceptualisation of Arab by European composers resulting in harmful consequences a century later (Figure 6).

Now to really bend the spoon of musicololgy, consider an analogous lineage in representation of Asian music, but how this is being reappropriated by Asian cinema (Figure 7).

In musical exoticism, this story happened over a couple of centuries; music was heard by live performance and sheet music shared globally by ship.

However, with computational scale and the reach of the internet, these social processes are vastly accelerated. Misinformation at critical times, such as a pandemic, can now spread globally in a matter of hours [23]. Resistance to harmful emergence may be unexpected creative emergence; we want to foster creative emergences that bring humanity together, and mitigate harmful emergence that divide us.

Happily, we have a language that unites critical theory, mathematical chaos, and computation: category theory—there’s a reason Spivak named his canoncial text, Category Theory for the Sciences; it is a grammar across sciences.

Here is our relational understanding of postcolonialism in graph form.

A singularity may be thought of from many perspectives, indeed, infinitely many; we are interested in understandin the interoperability between intentional and heuristic agency in the system.

Consider this system in terms of three things:

A category-theoretic way of measuring the stabilty of the system might be to ask:

For whom is this analysis FAIR?

This is the minimal model of structured intelligence governance we shall concern ourselves with.

Think on this. In over 10 years of working with data, I’ve never seen an organisation able to answer this question about their analytics department.

We want to govern the system opinionatedly towards humans exercising intent, rather than falling on meaningless convention or social hegemonies of oppression, and we wish machines to apply their heuristics in alignment with human intent. We consider other outcomes as emergences.

An intelligence-governance question might be to ask:

Which rules need to be updated to

- foster creative, virtuous emergence:

- govern humans to employing intent when required;

- and ensure automata do not deviate from expectations, in particular preventing harm to humans.

For all the talk of ethical “AI” there is scant attention paid to what is FAIR (as defined in Table 1) for each human in the singularity, and just how important observability of intention is.

For example, IT systems are security oriented, and it may well be sensible to operate from the principle of least privilege [12]. However, system access is very different to analytical access. Usually there is a legitimate reason to access the data, as required by the principle of least privilege, however where to find the required data is unclear, so exploration of several sources might be needed. Without knowing what to request access to, the analyst is obstructed in analysis.

We now consider a couple of motivating examples, before considering the benefits and pitfalls of measuring FAIRness.

Most any department or lab has at least one computational hotshot. For example, an applied science post-doc who is particularly good at open-source, or an analyst who has memorised scikit-learn [24] tutorials.

hotshot gif

entity map at starting point: all but region & displacement attributes were open to Garima–> we must get better than that immediately or Garima has less power to get her message out.

In paper, we focussed on observations defined by one person at one work instance, in this case defined to be a week in which that person might need to access the analysis to progress the project. However, formal framings open up a dizzying array of possible measures.

Each measure comes with a framing, each arrow a ruleset. We need to marry critical frameworks, such as epistemic injustice, with data science as a matter of imperative in order to ask what these framings and rulesets should be. Harm to humans and harm to our environment are not science fiction dystopia of robots, but banal and devastaing automata unleashed at scale on humans with no accountability for ungoverned emergence.

Contributor acknowledgement: This argument was improved by a discussion with my brilliant neighbour Álfrún Freyja Eldberg Agnarsdóttir, age 9, who highlighted that out of notifications, logging in, and advertising, all are intrusive, and the worst is logging in. The effect of this intrusive barrage of technology on children seems dangerously unmonitored.↩︎

As I prepare to apply for dual citizenship via my father’s parents, Holocaust refugees, this resonates deeply, German society enabled the Nazis through people following rules, rather than questioning if they should.↩︎

Contributor acknowledgement: This argument was improved by a discussion with my brilliant neighbour Álfrún Freyja Eldberg Agnarsdóttir, age 9, who highlighted that out of notifications, logging in, and advertising, all are intrusive, and the worst is logging in. The effect of this intrusive barrage of technology on children seems dangerously unmonitored.↩︎